Between Archive and Urgency

Richard Niessen & Kylièn Bergh

Figure 2. [unkown], Against Racism & Against Facism, [digital image announcing a march on the 24th of March in 2025]. 2025.

We live in turbulent times. As social and political tension rises, people seek other perspectives and find them in the traces of earlier social struggles. We consult our heritage stored in archival institutions, which in turn reinvigorates our collective memory. At the same time, we see how the expressions of earlier social movements are constantly being mobilised on the streets again. The posters of squatting movements are reprinted, and an illustration once kicking out the nuclear arms program is redrawn to kick out Fascism. It reminds us that our ‘wicked problems’ are deeply rooted and that racism, polarisation, wars, genocide, poverty and climate change are not new at all. In mobilising our visual language to address urgent matters, graphic designers can play a crucial role. Yet the dependency on historic material also triggers questions. How can archival material, for example, be used to raise social awareness, and what is the role of graphic designers in all this? How open are archives, and how can designers make them easier to use and more relevant to society? Can working with archival material contribute to a language of solidarity, and also, to what extent should we continue to rely on priorly existing material instead of pursuing visual languages reflecting the times we live in?

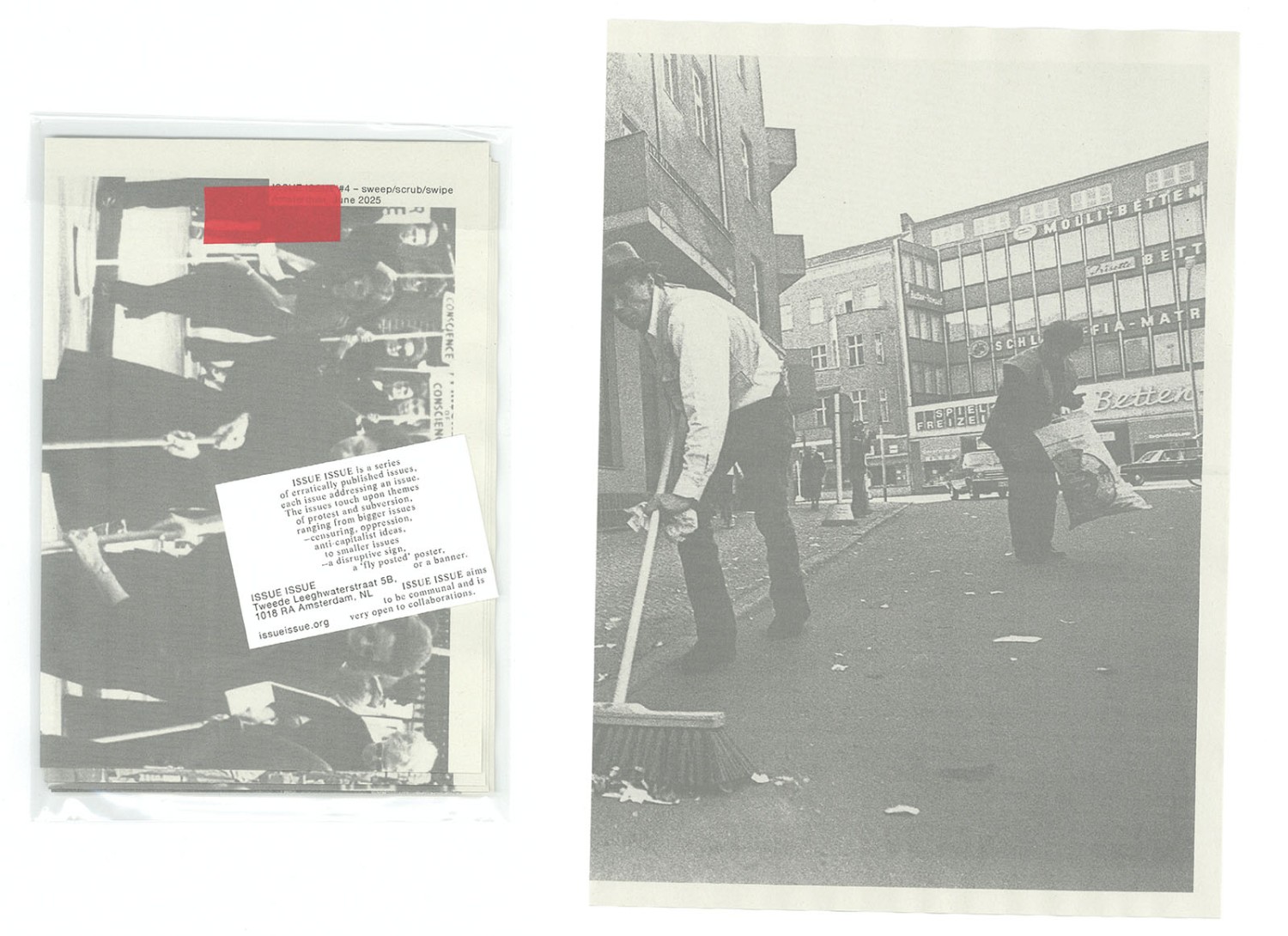

With their reach in public media, graphic designers can play a key role in republishing archival material. Projects like ‘Open Archief’, for instance, even actively encourages artists and designers to engage with historical collections. Initiated by the Nieuwe Instituut, Sound & Vision, and the International Institute of Social History, this collaborative project promotes the use of digital archives and stresses the importance of access to shared heritage. Take as an example the publication series ‘ISSUE ISSUE,’ designed by Geke Zaal, that actively republishes archival material in order to draw parallels between issues of the past and the present. Similarly, Marius Schwarz’s design for the publication of the ‘Open Archief’ revives historical material while underscoring its social relevance. Or see how new archives, exemplified by The Black Archives, emerge to emphasize the social urgency of material culture. By representing archival material, designers can uncover overlooked stories and help to visualize them.

However, working with archives is not just about celebrating heritage—it can also be a form of critical inquiry. Workshops, publications, performances, and installations reactivate historical material and turn it into collaborative spaces. This is exemplified by Werker Collective, for example, revisiting the queer workers’ emancipation struggles of the 1980s and 1990s, or in how Experimental Jetset draws inspiration from a legacy of anarchic squatting movements. In addition, see how knowledges obscured by normative perspectives on our bodies and desires are instrumented as a vocabulary of solidarity in the publication series Archival Textures found by Tabea Nixdorff, how questions of belonging and displacements are gathered in the magazine ISSUE: An Archive Of Collective Struggles, or how Farida Sedoc infuses historical research with contemporary social struggles to show that the revaluation of archives is not only retrospective but also speculative. By unearthing feelings and experiences from the past, designers can imagine alternative futures. Design is no longer merely a means of supporting protest—it is protest.

The protest movements of the past have left their mark on the activism of today. This was made apparent in the exhibition ‘Past Disquiet’ at Framer Framed. Using archival material, the exhibition uncovered artists’ involvement in anti-imperialist solidarity movements. It revealed how the visual language of activism—often rapidly made by amateurs—focuses on easy reproduction. Using a mobile screen-printing press, Farah Fayyad, who was involved in designing the exhibition, takes this approach to the streets. The exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, ‘Everyday, Someday, and Other Stories: Collection 1950–1980’, shows similar art that celebrates and remembers protest movements, focusing on how easily they can be copied. Thus, preceding protest movements influence our contemporary expressions of solidarity. But should we cling on to our past to highlight the relevance of our problems, or can we devise other ways to express urgency in a visual language that is in line with contemporary means of communication?

Practitioners as Yuri Veerman or Studio Pinopotato exemplify the latter standpoint. In using current media trends, they explore the repurposing of unambiguous design to tackle social issues. However, how today’s organised protest groups—like Greenpeace, Amnesty International or Milieudefensie—communicate is very different from the immediate approaches of the past. In conforming to media aesthetics, it may reach out to a wider audience, yet by blending in it may also remain unnoticed and lose its visual and cultural impact.

Moreover, while the material objects of protest movements have always been ephemeral by nature, much contemporary protest takes place on digital platforms. It is decentralized and temporarily fleeting material. Often, default typefaces are placed on top of found footage or snapshots from previous events. Without adequate design approaches, emojis and memes are now prominent in communications about urgent matters. To make matters worse, the actual public space for messages of social relevancy has virtually disappeared. Whereas once spaces were reserved for announcements without commercial intent (‘vrije aanplak plaatsen’), used by social organizations as much as protest movements, our public domain has seen an increasing commercialization throughout the past decades. Poster columns made way for electronic and digital billboards (mupi) in which advertising is affordable only by commercial organisations. Our cities, as much as our digital domains, are privatised environments, restricting the possibilities of social organisation.

So, what can be learned from revisiting archives? A fresh group of activists is appearing, and a new group of designers is trying out ways to make activism noticeable in both the real world and online. Are we witnessing the emergence of a new, visually rich language of protest, or are we stuck with the language of social unrest that preceded us? Can we reinvent a language that is suitable for raising socially relevant issues in this interplay between archive and urgency?

_____

This article, written by Kylièn Bergh and Richard Niessen, introduces the panel discussion It’s All Graphic: Between Archives and Urgency. This event is organised by the Wim Crouwel Institute on the 10th of September 2025 and hosted by Pakhuis de Zwijger in Amsterdam. During the event graphic designers Marius Schwarz, Farida Sedoc, Studio Pinopotato and Geke Zaal will share insight on their experiences balancing the working with archival matters and social urgencies.